Heraclitus Standing in the River

Before we bring the pre-Socratic giants of thought into collision, let us first listen to three of them: Heraclitus, Pythagoras, and Xenophanes.

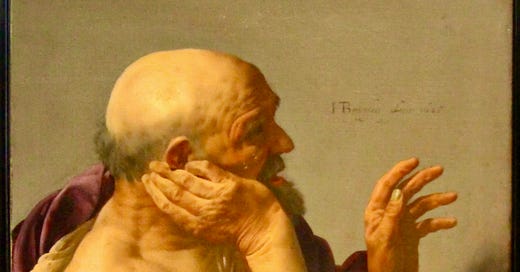

Heraclitus by Hendrik ter Brugghen (1628), Rijks Museum Amsterdam, Photo by bertknot/public domain.

Incidentally, the panorama of pre-Socratic philosophers resembles the heroes of America’s Justice League—heroes battling evil with all the elements at their disposal: fire, water, earth, and breath. Heraclitus chose fire as the fundamental substance of the world, emphasizing the dynamics of movement, transformation, and perpetual conflict. And yet, paradoxically, he is remembered not for flames but for water—especially his famous metaphors about the river. It’s a bit like if director Michael Bay (Pearl Harbor and Bad Boys) were known not for the excessive explosions and over-the-top flames in his films but for delicate landscapes, say, in an adaptation of War and Peace. Clearly, the fate of how philosophers are remembered can be as unpredictable as the chances of getting a table at a trendy restaurant on a Friday night.

Personally, I remember Heraclitus’s river of time most vividly from Illumination by Krzysztof Zanussi, one of the most significant films I watched in my youth. It left an unforgettable impression on me and inspired me to study philosophy. Incidentally, this cult classic from 1973 features the most renowned Polish historian of philosophy, Władysław Tatarkiewicz, who explains the concept in the opening monologue. Illumination is a state of enlightenment—a direct experience of truth about the world, oneself, being, and time. When I watched the film fifteen years after its premiere, at the beginning of my studies, I saw myself in the protagonist—torn while searching for life’s path, grappling with the challenges of early fatherhood of a child with disabilities, the necessity of supporting a family, and emerging questions about the meaning of life, freedom, and free will. The illumination of the film’s protagonist, Franciszek Retman, a physics student, is precisely a Heraclitean illumination. In this scene, the protagonist stands in a river. By the way, I wonder what Heraclitus would have said if he had seen Illumination. Perhaps something along the lines of: “You can’t watch the same movie twice”?

Heraclitus hailed from Ephesus, a city that offered its residents an array of attractions: a world wonder in the form of the extraordinary temple called the Artemision, the wild Ephesia (a local version of Bacchanalia or the Brazilian Carnival), and the Kaystros River, in which the philosopher must have dipped his feet more than once. As an aristocrat and member of a royal family, Heraclitus could afford the luxury of lying on a marble couch and pondering the nature of things. Like all pre-Socratics, he wrote a Peri Physeos (On Nature), as this was apparently a universal title back then—the philosophical equivalent of today’s self-help books like Philosophy for Dummies in a Weekend. About 130 of his sayings have survived, including one great principle (“everything flows”), one famous statement (“You cannot step into the same river twice”), and one quip that sounds as though the philosopher invented a meme about Russia: “War is the father of all things.”

The First Principle: Universal Variability

The first principle speaks of the constant motion and dynamism of the world, often referred to as universal variability. It describes the ceaseless transformation arising from the contradictions within things and phenomena, as well as the primacy of change (fire symbolized this transformation). In a sense, this idea deepens Anaximander’s notion of the disappearance of elements, their struggle, and constant becoming. Heraclitus went further, elaborating on the concept of tension created by the struggle of opposites and the force that both drives the world and keeps it in a state of perpetual balance. Plato summarized his thought succinctly: “Nothing is; everything becomes,” while Aristotle wrote equally concisely: “Nothing exists in a permanent way.”

The Polish poet Helena Poświatowska once wrote: “Heraclitus—my friend, you taught me to love fire and to die every moment.” For Heraclitus, fire, death, and transformation into something new manifested themselves in conflicts—he famously said, “War is the father of all things,” rendered in ancient Greek as polemos pater panton. One might say that Heraclitus was the first philosopher to understand that the world resembles the latest version of a computer game, like Path of Exile 2: there is no “level of permanence,” and the greatest adversary is… the ever-looming change. Recently, a certain billionaire learned the dangers of this all too well.

Heraclitus believed that the cosmic fire had its counterpart in the soul. However, in weak individuals, its strength is diluted by the watery element, which manifests simply as stupidity. This notion bears a striking resemblance to much later musings by Nietzsche. In fact, Nietzsche’s philosophy reflects many Heraclitean themes. Heraclitus wrote: “We fear a single death, yet we have already succumbed to many,” a sentiment echoing Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence.

Once, a friend of mine—a philosopher and writer named Marcin Polak—explained this idea of eternal recurrence to me. We were strolling through Warsaw at Marcin’s brisk pace, which I could rarely keep up with. At one point, stopped by the traffic lights, Marcin said, “According to Nietzsche, we aren’t standing at this light for the first time. We’ve stood here countless times before and will continue to stand here for eternity, watching the lights change before our eyes.”

It sounded almost like a loop from Groundhog Day starring Bill Murray, where the protagonist experiences eternal recurrence by reliving the same day over and over. Every action, though it seems unique, in reality repeats itself endlessly.

Heraclitus and the Concept of Logos

Heraclitus was the first philosopher to introduce the concept of logos, an important term for the development of philosophy. At this stage in the history of thought, logos was still a fresh term, free from the many layered meanings it would acquire later. It isn’t as complicated a word as it may seem at first glance. Logos would go on to become a central concept in Greek philosophy, and later, during the Christian era, it would come to define all philosophy.

For Heraclitus, logos was nothing other than the rationality of the world—a rule of rules, a supreme principle, something that governs everything through everything. To Heraclitus, the key to the universe lies within ourselves. Therefore, to understand the world, one must first know oneself. This makes us an analogy of the world.

In this thought, Heraclitus emerges as a much more intriguing philosopher than his fellow pre-Socratics, as he directed inquiry inward—toward ourselves—pioneering a path of introspection. This makes me wonder if Heraclitus could be considered the first “coach” in the history of philosophy. He might have said something like: “Understand yourself, and you will understand the world”—a slogan that would look great on corporate district billboards.

Heraclitus also emphasized that logos pertains to all of us, which implies that philosophy is for everyone (though, of course, some school systems might disagree). His famous saying about the river can also be interpreted as: “We are ourselves and yet not ourselves,” or in another translation, “We both are and are not.” This is akin to drinking the same cup of coffee every morning—it changes slightly, but in the end, it feels the same.

From his conviction about constant change came the phrase, “everything flows,” or in ancient Greek: panta rhei. This is symbolically captured in the saying: “You can’t step into the same river twice.” The latter is more of a folk version of Heraclitus’s truth, akin to the Polish saying, “The rooster thought of Sunday…” Another saying, also attributed to Heraclitus, is: “The sun rises anew every day.”

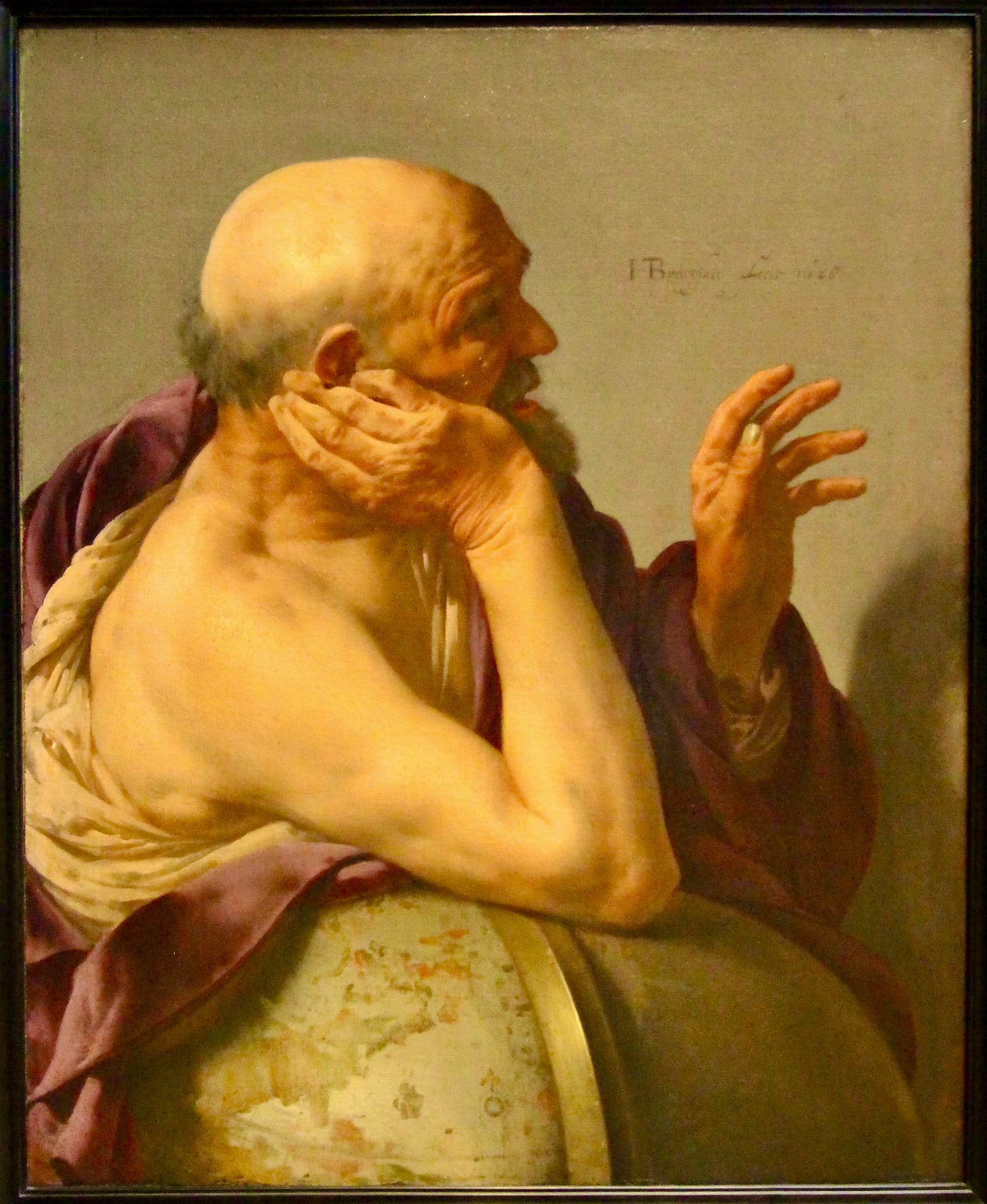

Democritus laughing and Heraclitus weeping, with a globe between them. Engraving by W. Hollar after J. van Vliet after Rembrandt van Rijn.

Heraclitus left behind another piece of wisdom that remains relevant today: “Knowledge of many things does not teach wisdom.” This could serve as the perfect motto for social media users.

From his premise that “from all, one; and from one, all,” Heraclitus derived a kind of indifference. He asserted that good and evil are the same and that, for God, everything is beautiful, good, and just. Perhaps Heraclitus was right because, ultimately, as he said: “Up or down, the path is the same.”

This idea can be compared to riding an elevator. Whether you press “up” or “down,” you’re in the same cabin, traveling along the same axis, always within your building. However, it’s wise to remember a warning found in a high-rise building: “Before stepping into the elevator, check that the cabin is on your floor.”

Heraclitus, with his sharp wit and aphorisms that could rival the best stand-up comedians of our time, never made it onto the list of Ancient Sages. Yet, if someone were to compile his fragments into one grand performance, it would undoubtedly be a show worthy of a standing ovation. Unfortunately, his brilliance wasn’t fully appreciated, partly because his sayings resembled the cryptic riddles of the Delphic Pythia, earning him the nickname “The Obscure.” If only we were all so “obscure”...

Apparently, Heraclitus was also a considerate brother. He gave up an inherited position in a municipal company (a cushy job akin to an MBA from a shady university) to one of his brothers, choosing instead to retreat from public life and dedicate himself to philosophy. However, it seems his decision stemmed more from disdain for Ephesus’s bureaucrats than selflessness. His younger brother was likely a convenient pawn in this strategy—why suffer the grind of politics when you can leave it to someone else?

Heraclitus retreated into a kind of philosophical retirement, leaving political matters to his brother. In parting, he left some choice advice for the citizens of Ephesus:

“Mad and senseless people! You’d do better to hang yourselves, all of you! Hand over the city’s rule to children—they’d surely manage it better!”

Disillusioned by the exile of his friend Hermodorus, Heraclitus abandoned Ephesus’s political life altogether and chose solitude in the mountains. There, he lived as a hermit, subsisting on roots, grass, and leaves. But even the best intentions can lead to unforeseen outcomes. Heraclitus’s diet led to hydrops, likely ascites caused by liver damage.

Forced to return to the city in search of treatment, Heraclitus devised a remedy as unconventional as his philosophy. He buried himself in cow dung, hoping to sweat out the illness. Unfortunately, instead of recovering, he died the next morning. Some accounts suggest that, after his death, his own dogs failed to recognize him and devoured his body. While this sounds like the kind of malicious gossip spread by his contemporaries, it’s worth noting that dogs don’t usually eat their owners, though the reverse is sometimes true—like in certain parts of China.

Heraclitus’s story, though tragic and tinged with dark humor, offers a poignant lesson: not everything natural is healthy, and withdrawing from society doesn’t always lead to success. His life, like his philosophy, was full of paradoxes, leaving us with much to ponder.

Heraclitus traveled extensively. One day, he made it all the way to China to meet Lao Tzu (Laozi), having read a review of his work, Tao Te Ching, in the Ephesian Scroll of Thought. Intrigued by the concept of yin and yang described there, he decided to investigate further. Lao Tzu, or Laozi, was the presumed founder of Taoism, who outlined the principles of cosmic order, social harmony, and personal peace and happiness. It’s hard not to notice the similarities between his ideas and Heraclitus’s theories, which emerged around the same time but in vastly different parts of the world. This, of course, hasn’t stopped us from speculating about unknown inspirations or even possible borrowings.

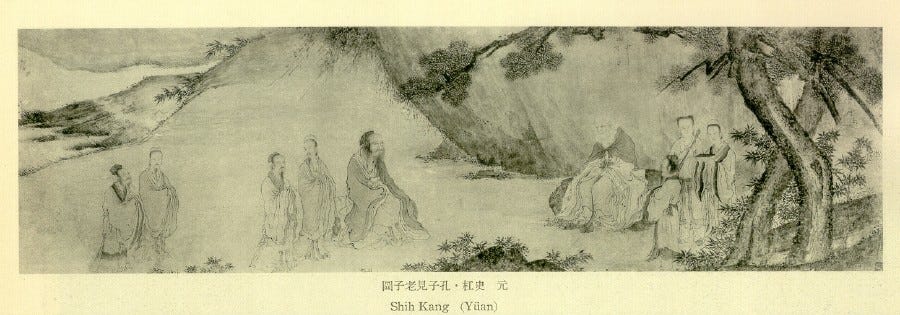

Confucius meets Laozi, Shi Gang (史杠), Yuan dynasty

Lao Tzu sat cross-legged in his mountain retreat, meditating. Heraclitus, weary from the long journey along the Silk Road—a modest 12,000 kilometers—sat down opposite him. After catching his breath, he blurted out the words that had been simmering on the tip of his tongue:

“Master, it’s quite evident that most of your ideas originate from translations of my work into Chinese. Could you be so kind as to at least credit your sources in the future? Or do you wish to set a precedent for your compatriots—imitating the West, copying its ideas, stealing others’ wisdom, spying, and passing off borrowed knowledge as your own?”

Lao Tzu, known for his reluctance to engage in unnecessary conversation, continued to sit cross-legged, gazing at the horizon. He remained silent for a moment, then finally looked at Heraclitus, as if gauging whether he truly understood the words he’d just spoken. At last, with a faint smile, he replied:

“Well, Heraclitus, it’s like your ‘everything flows,’ only without spilling over the edges. Yin and yang are nothing more than your opposites—they work together rather than against each other. There’s no good without bad, no day without night.”

Heraclitus paused to reflect for a moment, then burst into laughter.

“You know what, Lao Tzu, maybe you’ve got a point, too. Just remember, though, that if you meditate too long, you’ll need months of traveling to restore balance, because sitting cross-legged makes your legs ache. It might help you understand that yin and yang aren’t just philosophy—they’re also a kind of gymnastics. Be careful with the hardships of life in this mountain solitude—an all-root diet could ruin your health.”

Ultimately, Heraclitus returned to Ephesus, where his cow-dung treatment awaited. Along the way, he had plenty of time to ponder how Taoism aligns with his theory of opposites. Their meeting might have been the beginning of a long, ongoing confrontation between cultures—a dynamic that fits into the order of the world like yin and yang, and sometimes, unfortunately, like Heraclitus’s strife of opposites: war.

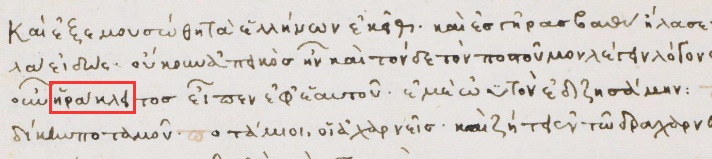

οὔκουν ἀπεικὸς ἦν καὶ τόνδε τὸν Ποστοῦμον λέγειν λόγον ἐκεῖνον, ὅνπερ οὖν Ἡράκλειτος εἶπεν ἐφ' ἑαυτοῦ: ἐμεωϋτὸν ἐδιζησάμην. 'So it was not unreasonable to say, of this Postumus, that saying which once Heraclitus applied to himself: "I went in search of myself".' Heraclitus quote, in the 'Suda', lemma 'postoumos' - British Library. Public domain - Wellcome Images Trust.